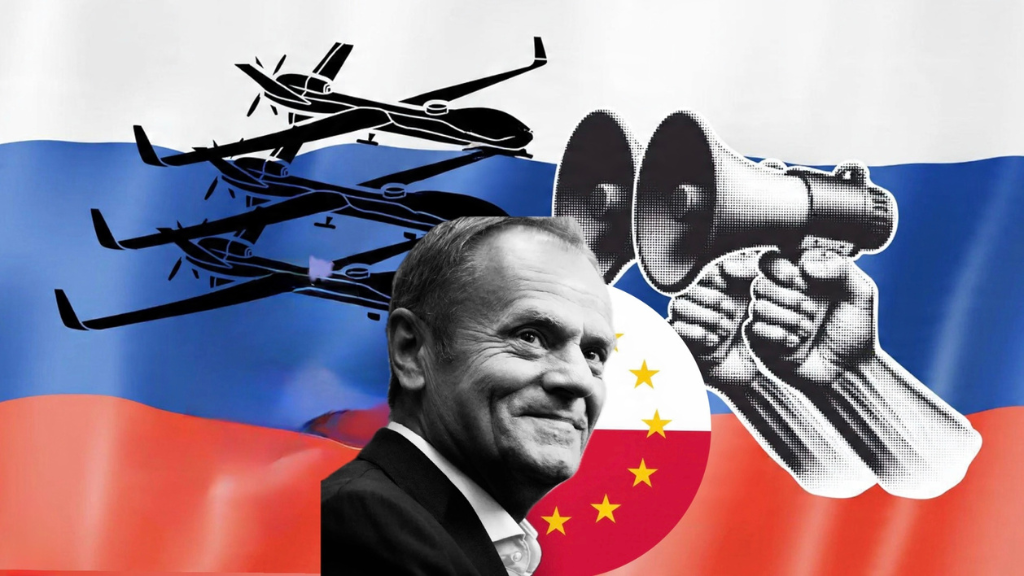

For years, Donald Trump directed blunt criticism at Europe from the campaign trail and podiums abroad. That rhetoric was often dismissed as provocation. But when his worldview was formalised in a National Security Strategy (NSS), the implications became harder to ignore. The document paints a bleak picture: Europe, it claims, will be “unrecognisable in 20 years,” hollowed out by what Trump describes as “civilisational erasure,” unless the United States intervenes to restore the continent’s “former greatness.”

Europe does face serious challenges. Trump is not wrong about that. Where his argument fails is in diagnosing the source of the problem and, by extension, prescribing the wrong cure.

The most pressing threats to Europe are not cultural replacement or immigration-driven decline. They are structural and self-inflicted: decades of underinvestment in human capital, political systems that sideline entire communities, and an unwillingness among elites to confront how demographic stagnation and economic exclusion reinforce one another. These are issues leaders often acknowledge privately but avoid publicly, choosing instead to debate surface-level symptoms rather than root causes.

A more accurate picture emerges when one looks beyond institutions and into lived experience. Across Europe’s post-industrial regions, working-class communities contend with shuttered factories, failing schools, unaffordable housing, and weakened public services. No group illustrates this failure more starkly than the Roma. As Europe’s largest and most marginalised minority, their treatment exposes a continental pattern: entire populations written off as expendable. When Trump claims to press on Europe’s weak points, it is these communities that confirm where the damage truly lies.

Where Trump’s Critique Lands and Where It Misses

The NSS argues that Europe’s “lack of self-confidence” is most visible in its posture toward Russia. On this point, the critique is not entirely misplaced. Europe’s caution toward Moscow stands in sharp contrast to its willingness to exert force internally, particularly against marginalised groups. That imbalance reflects a deeper uncertainty about European values.

A confident Europe would defend pluralism, democracy, and the rule of law without hesitation. Instead, many governments resort to securitisation at home while avoiding confrontation abroad. Roma communities are frequently the targets. In Slovenia, a localised incident was enough to trigger national legislation increasing surveillance and policing of Roma neighbourhoods. In Portugal, far-right leader André Ventura used openly discriminatory rhetoric during his presidential campaign. In Italy, Matteo Salvini built political momentum through persistent anti-Roma messaging. In Greece, police violence against Roma youth has followed even minor infractions.

This pattern is revealing. European states often overcompensate domestically for their geopolitical caution, projecting strength inward where resistance is weakest.

Trump’s NSS also highlights Europe’s declining share of global GDP, from roughly a quarter of the world economy in 1990 to around 14 percent today. Regulation and ageing populations contribute to this trend, but they are not the core issue. The deeper problem is Europe’s systematic failure to mobilise its own human resources.

Around 12 million Roma live in Europe, forming its youngest demographic group. Yet structural barriers and discrimination continue to block access to education, formal employment, and entrepreneurship. This exclusion persists despite clear evidence that Roma communities participate successfully when given access to capital, training, and legal protection.

The economic cost is not theoretical. In countries such as Romania, Slovakia, and Bulgaria, Roma unemployment rates exceed national averages by roughly 25 percentage points. Aligning those figures would yield an estimated GDP gain of up to €10 billion. At a time when Europe loses roughly two million workers annually, sidelining this labour pool amounts to economic self-harm.

Trump is correct that Europe’s economic weight is shrinking. But the decline will not be reversed by cultural crusades or exclusionary politics. A continent that abandons millions of its own people cannot remain competitive.

Democracy’s Blind Spot

The NSS warns of democratic erosion in Europe, framing it largely as a response to speech restrictions and constitutional barriers against extremist movements. This framing misidentifies the real democratic deficit.

Europe’s most glaring shortfall is representational. By population size, Roma citizens should hold more than 400 seats across European legislatures. Yet the European Parliament which allocates seats to countries with fewer than one million residents includes no Roma representatives at all.

This absence has consequences. Political exclusion depresses voter registration and participation, producing institutions that do not reflect the societies they govern. Economic marginalisation, in turn, leaves communities vulnerable to coercion, vote-buying, and political manipulation. Democracy weakens not because it is too restrictive, but because it fails to include.

A Europe that wastes human potential cannot compete globally. One that suppresses segments of its electorate cannot credibly claim democratic legitimacy.

What Europe Actually Needs

Trump’s proposed remedy empowering far-right, pseudo-sovereigntist movements would exacerbate rather than resolve Europe’s crisis. The empirical record is clear. Where xenophobia drives policy, economic and democratic performance suffer.

In the United Kingdom, Brexit propelled by anti-immigration rhetoric has reduced GDP by an estimated 6–8 percent compared to a counterfactual scenario of continued EU membership. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s exclusionary governance has coincided with stagnant growth, mounting deficits, and frozen EU funds. Far from restoring strength, exclusion erodes resilience.

Rehabilitating ideological currents that the United States once helped Europe defeat would not renew the continent. It would deepen dependency first on Washington, then on Moscow.

Nor can Europe rely on nostalgia for liberal order or ritualistic multilateralism to survive an increasingly transactional global system. What it needs instead is inclusive realism: the recognition that investment in people is not moral indulgence but strategic necessity.

China’s rise illustrates this logic. Sustained investment in health, education, and employment expanded human capital and reshaped global power balances. Europe cannot afford to discard its own population potential while expecting continued relevance.

The real choice facing Europe is not between liberalism and the far right. It is between compounding decline through exclusion or beginning renewal by investing in those long treated as disposable. The continent’s future depends on which path it chooses.