Predictions of impending global conflict are not new. Every decade carries its own sense of looming catastrophe, shaped by the anxieties of the time. Yet dismissing today’s warnings as another cycle of alarmism would be a mistake. What distinguishes the present moment is not the mere presence of conflict, but the way multiple crises are converging within an international system that is increasingly brittle, polarized, and interconnected.

The global order entering 2026 does not resemble the relatively compartmentalised world of the Cold War, where conflicts, though intense, were often geographically and ideologically contained. Today’s wars bleed across borders through markets, migration, technology, and information. Even conflicts that do not escalate into full-scale wars now carry consequences that travel far beyond the battlefield.

A Fragmented Security Landscape

The idea that the world is heading toward one singular, defining war oversimplifies reality. Instead, what is emerging is a landscape of simultaneous, overlapping conflicts, each reinforcing instability in others.

East Asia, West Asia, Eastern Europe, and parts of Africa have all become high-risk theatres. None operates in isolation. Tensions in the Taiwan Strait are tied to the broader strategic rivalry between the United States and China. The war in Ukraine is embedded in a wider reconfiguration of Europe’s security architecture and global trade. Instability in the Middle East continues to disrupt energy markets and political alignments far beyond the region.

This fragmentation makes the system harder to manage. Diplomatic bandwidth is finite. Economic buffers are thinner. And crisis fatigue has dulled international responsiveness, particularly toward conflicts that unfold slowly or outside the media spotlight.

Taiwan and the New Face of Conflict

Among all potential flashpoints, Taiwan stands out not because war is inevitable, but because conflict no longer requires invasion to be devastating. Coercive measures such as maritime pressure, cyber operations, or selective blockades could achieve strategic objectives without a single formal declaration of war.

The global implications of such actions would be immediate. Taiwan’s central role in semiconductor manufacturing means even limited disruption would reverberate through global supply chains. Manufacturing slowdowns, rising costs, and technological bottlenecks would quickly translate into economic stress across continents.

In this sense, Taiwan represents a broader shift in warfare itself: power is increasingly exercised through economic leverage and technological choke points rather than territorial conquest alone.

The Middle East and the Logic of Escalation

West Asia continues to operate under a logic of escalation rather than resolution. The Israel–Hamas conflict has already demonstrated how quickly localised violence can draw in regional actors. Tensions between Israel and Iran, briefly visible in 2025, remain unresolved and volatile.

The strategic danger lies less in immediate large-scale war and more in the cumulative effect of instability. Maritime chokepoints such as the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf remain vulnerable to disruption. Even temporary insecurity in these routes has outsized consequences for global energy prices, shipping costs, and inflation.

Moreover, the political symbolism of the Israel–Palestine issue continues to polarise societies far beyond the region. Information warfare, narrative battles, and ideological mobilisation have become integral components of the conflict, deepening global divisions at a time when consensus is already scarce.

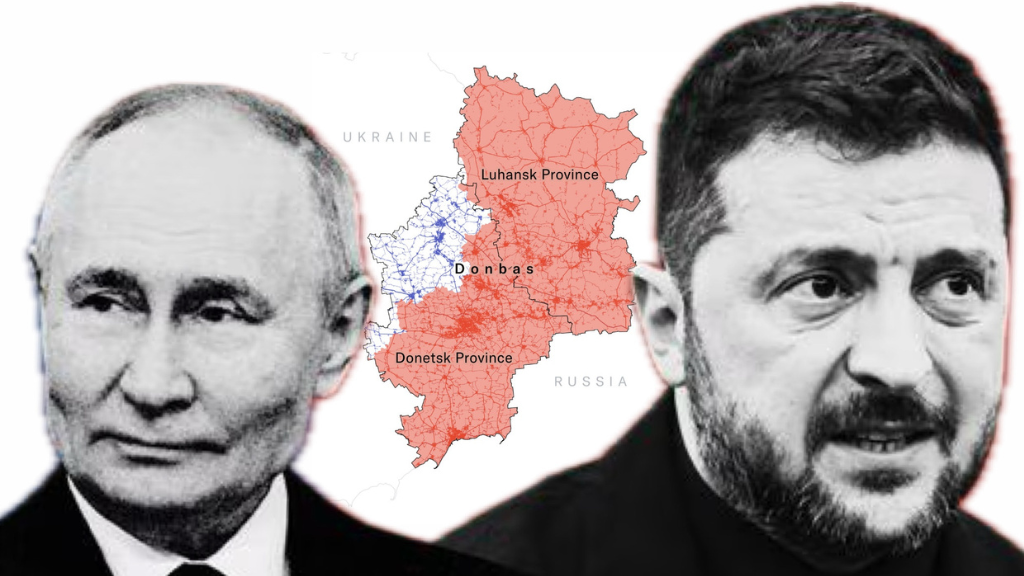

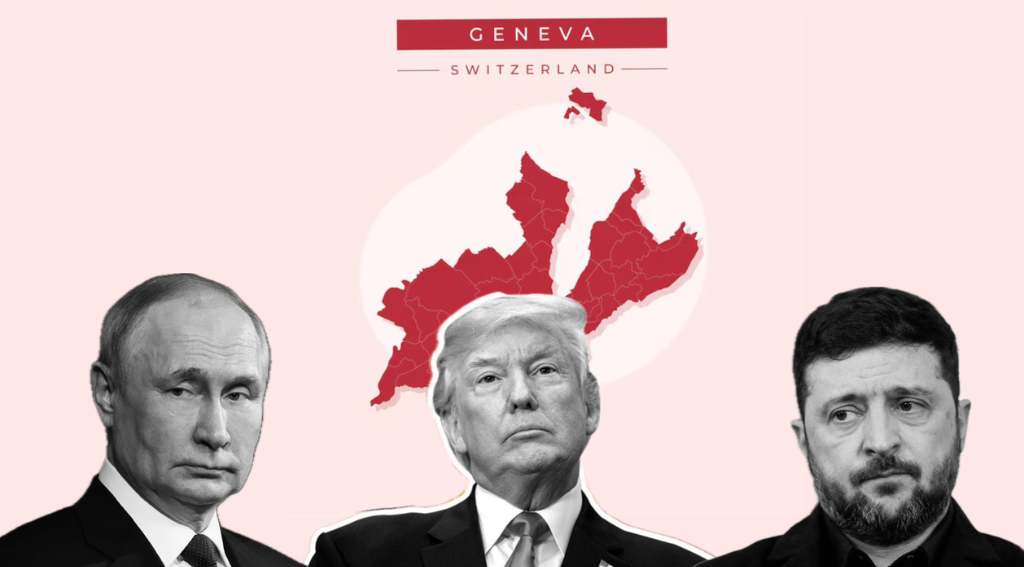

Ukraine and the Normalisation of Economic Warfare

The war in Ukraine has gradually shifted from a dynamic battlefield conflict to a structural feature of global politics. Its most enduring legacy may not be territorial outcomes, but the normalisation of sanctions, counter-sanctions, and trade realignment as permanent instruments of state power.

These measures have altered food, fertilizer, and energy markets in ways that are unlikely to reverse even if active hostilities diminish. Europe’s militarisation, Russia’s economic reorientation, and the deepening of bloc-based trade systems point to a world where economic efficiency increasingly gives way to strategic loyalty.

In this environment, globalisation has not collapsed, but it has hardened into competing spheres.

The Wars We Choose Not to See

While major-power conflicts dominate attention, some of the most destabilising crises remain underreported. Sudan, the Sahel, Yemen, and eastern Congo continue to experience prolonged violence with devastating humanitarian consequences.

These conflicts produce mass displacement, radicalisation, and state collapse, conditions that rarely remain contained. Migration pressures on Europe and the spread of extremist networks across Sub-Saharan Africa are not accidental by-products; they are predictable outcomes of sustained neglect.

Ignoring these wars does not reduce their impact. It merely delays recognition of their consequences.

Implications for India and the Global South

For countries like India, the challenge posed by this environment is indirect but profound. Energy price volatility, supply-chain disruptions, and food insecurity translate quickly into domestic economic and political pressures. Semiconductor disruptions in East Asia would affect industrial ambitions, while instability in West Asia has immediate implications for energy security and diaspora populations.

Strategically, intensifying rivalry between major powers places growing pressure on middle powers to align technologically, economically, and militarily. Preserving strategic autonomy in such a context becomes increasingly difficult, even as it remains essential.

At the same time, instability in India’s extended neighbourhood, from Afghanistan to politically fragile neighbouring statesadds another layer of vulnerability, particularly with respect to terrorism, border security, and refugee flows.

A System Under Strain

War is coming, not necessarily in the form of a single, dramatic global conflict, but as a persistent condition of international life. The danger lies in accumulation rather than explosion: multiple conflicts, economic shocks, and political fractures reinforcing one another over time.

In a world as interconnected as today’s, insulation is largely an illusion. Preparedness, diversification, and resilience have become the core requirements of stability. The ability to anticipate disruption, rather than merely react to it, will determine which states navigate the coming years with relative security.

The warning signs are visible. Whether they translate into catastrophe depends less on inevitability than on choices still being made.